Get All Your Employees to Ask Questions: 5 Steps

INSEAD innovation professor Hal Gregersen describes how you can systemize question asking to encourage creativity and solve problems.

Is your company starting to stagnate? You may not be asking enough questions.

According to Hal Gregersen, a leadership and innovation professor at INSEAD and co-author of the book "The Innovator's DNA," asking questions is a practical tool to help you come up with new ideas, solve problems, and gain different perspectives.

To that end, Gregersen developed a questioning method, which he calls "Catalytic Questioning." In a recent article in the Harvard Business Review, he describes how you can use Catalytic Questioning to nurture creative brainstorming, unearth new directions for your team or business, engage your employees, and determine innovative solutions.

Here's how to implement this strategy:

1. Be Question-Centric

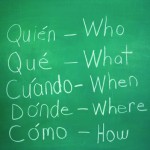

The method starts with gathering your team around a white board or flip chart, and encouraging everyone to ask questions about a particular problem in a rapid-fire style. Leave all assumptions at the door. The point is to bring "fresh eyes through fresh questions."

Click Here to Learn More

2. Engage Head and Heart

Pick a problem that your team cares about and wants to solve. Make sure the "opportunity," or problem (if you're not an optimist) truly does not already have a solution.

3. Question Everything

Use this time to only ask questions. Gregerson calls this "pure question talk." Have one team member write down verbatim each question that's asked. No one should retort with answers. Just keep the questions coming. Your goal should be to collect 50 to 75 questions, and to make each one better than the last. Don't give up. Push through when your mind goes blank and ask even more provocative questions. You'll need patience and persistence to exhaust your group's questioning "capacity." The exercise should take 10 minutes to 20 minutes.

4. Find the Catalyst

Step back and pinpoint the most "catalytic" questions. These are the questions that the group cannot answer--the ones that will "disrupt the status quo" if you do answer them. You should then cut your list down to just three or four.

5. Come Up With Answers

Now that you have a focused question for a particular problem, it's time to solve it. This step will be different for each company, depending on how you like to gather information. If you like to observe, go out in the field and "systematically observe" to get answers. Or you can get fresh ideas by networking; talk with diverse groups who don't think and act like you to get new perspectives. Then, start working on a few prototypes for "fast, cheap, virtual experiments," and get feedback on which one might be best.

After these steps, regroup with the answers you've come up with and brainstorm. Gregersen says you should pull together "all your new input" to create a better solution. If needed, repeat.